Mrs. Franklin Roosevelt of New York Builds a

Workshop to Glorify an Ideal

Craftsman Magazine 1932

One day, six

years go, the life story of a great woman began to carve

itself in wood. Mrs. Franklin Delano Roosevelt passing

through the small community of Hyde Park, New York, in late

October was impressed with the care-free idleness of lank

farmer boys loafing on the Post office steps. Inquiring of

the passing constable she learned, “oh, harvestin’s done.

Nothin’ now till Spring sowin’.”

|

Hyde Park was

a rural section with arming its chief concern, and therefore

its citizenry saw nothing unusual in the construction of a new

road through one of the meadows some few weeks later. It was

not until a cottage and a two story workshop had been erected

and young boys of varying ages and dimensions invited to

Val-kill to learn the art of craftsmanship, that a stir

rustling the countryside cleared off the Post Office steps.

Boys were wanted! All-year-round jobs were offered! Mrs.

Roosevelt had established a community workshop where the

manual arts---with woodworking in highest favor---could be

learned. |

|

Boys, to learn

woodworking, must have instructors. For that purpose expert

craftsmen were employed. But Mrs. Roosevelt did not stop

there. Her primary purpose accomplished, she went further in

deciding to market the furniture her shop produced.

While her

courageous ideal in fostering this group of woodworkers was to

direct the youth of this community into a craft, she foresaw

its practical application and prepared to make furniture of

such artistic beauty and fine workmanship, it would have a

market value and be treasured for generations to come. With

romance of this ideal in her heart, she found an art to

translate it and, with business acumen, a public to buy it.

Mrs. Roosevelt

made Val-kill all the more significant when she chose to

reproduce a definite style and period of furniture. Wisely,

because of the timely interest in American antiques, she

picked Early American.

In the

workshop at Val-kill power tools were installed and master

craftsmen employed. While a complete set of machines was set

up for general use of the shop, each expert had another set

comprising a lathe, bench saw, and planer for his own use,

installed on his own bench. The expert and his individual set

of tools are as inseparable as the doctor and his

instruments. Tools to him are sacred things. Now and then

“Tool Day” is formally declared and the machines are cleansed

and made ready for another two or three weeks. At first the

boy apprentices admitted to regular duty and placed on the

weekly pay roll, were little more than sightseers. They

strode about gazing in awe at the miracles of lathe and band

saw. But they enjoyed spending their hours in what seemed at

first to be a mechanical zoo, and in time one boy showed a

preference for lathe work, another for finishing, still

another took to carving and his enthusiasm and aptitude for

the work prompted him to go further, study design in New York

city. Today he is an expert.

Associated

with Mrs. Roosevelt at Val-kill is Miss Nancy Cook, furniture

designer, draftsman, and general manager. Upon her rested the

responsibility of being at once, studious and creative, and

keeping her eye on what the public will buy. Armed with

pencil and paper she visited many museums, exhibits, private

homes finding rare pieces, sketching rough notes and

dimensions here and there. After such a tour, she returned to

her office in a New York skyscraper on Madison avenue, swept

her enormous desk clear and went to work making full size

drawings for dozens of projects. With a sharp eye for

utility, Miss Cook selects pieces that can be adapted to

practical present-day sues, rather than furniture of the

ornamental variety With her own drawings, to full scale,

under her arm she sets out for Hyde Park. But long before she

crosses the meadow approaching Val-kill, she has decided which

one of her craftsmen gets to do the job. If the piece in the

making is a desk, Miss Cook assigns the work to the craftsman

who does that type of construction with the greatest skill.

Once the

drawing is presented to the chosen craftsman, the

responsibility of handing every operation is his. From

selecting the most suitable pieces of kiln-dried wood in the

cellar of the shop to polishing down the last coat of wax or

varnish, the piece never leaves his hands. There are no

specialists for each operation, for mass production is not

used at Val-kill.

Somewhere on

each completed piece of furniture turned out, carefull

inspection will reveal to you, the name of “Karl,” “Otto,” or

“Frank,” or perhaps the first name of some of the other

members of the group. Its only trademark is the name of the

man who built it. And “trademarking” is done with pride and

calls for ceremony at Val-kill.

Arriving on

the scene with a new design, Miss Cook dons her work smock and

gets the spirit of a true craftsman, helping out here and

there, and, unable to resist the urge of every true craftsman,

in watching the turning of a table leg, gets the urge to have

the feel of holding the chisel. Miss Cook’s versatile

abilities urge her on to help the next man at his carving on a

dining-room service table. Later she lends a hand in the

finishing of a table top---where the photographer caught up

with her and took the accompanying view. Meanwhile Mrs.

Roosevelt is directing work in the shop and inspecting a

ladder-back chair that is being shellacked.

In speaking of

the manner in which her furniture is built, she said, “by it,

your great-great grandchildren will still remember you,

whereas much modern furniture will not last a decade.”

If it is built

properly, declared Mrs. Roosevelt, a piece of furniture will

last indefinitely, perhaps hundreds of years. While much

furniture will loosen at the joints, warp out of shape and

even split Val-kill furniture is built to escape the ordinary

fates. Ask a Val-kill craftsman why his furniture will last,

and he’ll point a proud finger to the mortise and tenon joint

he is fitting in the rungs of a ladder-back chair, or in the

cross bars under a table.

Dovetailing is

also in high favor among these woodworking artists. The desk

I sat by in listening to Mrs. Roosevelt tell the story of Hyde

Park, had concealed dovetail joints. Wood warps. Every

professional, every amateur knows it, but few can do much t

prevent it. After experiment these craftsmen found a way to

keep the drop leaves of a seven foot diameter table from

warping. Underneath the leaf and across the grain a strip of

wood acting as a slip-joint batten is fitted and glued only at

one end to hold it in place and yet allow for natural

expansion and contraction of the wood.

Some of the

products of her shop, Mrs. Roosevelt has succeeded in placing

on display at museums in New York City. Recently she has

shipped furniture to Czechoslovakia and Hawaii.

Mrs. Roosevelt

is not the only woodworking fan in her family. Her husband,

Governor Franklin Delano Roosevelt, follows it as his hobby to

give him relaxation from his strenuous days in the state house

at Albany, New York. His hobby, however, takes a different

path. Perhaps because he feels there is enough furniture in

the family now, or more likely because of his boyhood fondness

for boats, in his leisure hours you may find him with infinite

patience whittling and carving out model boats.

Legends are not built in a day. Mrs. Roosevelt has much work

before her in building up the legend of Early America. I wish

every craftsman who reads this story could have sat across

that secretary desk where I did and heard this great woman

speak of her plans for the future, how she hopes to

immortalize the legend of America, not as we see it in the

records of Congress, not as it stands in the monuments on our

landscapes, not as our historians put it in books, but more

vividly, much closer as we see it in the works of the

craftsmen of the earlier day, in the things they made with

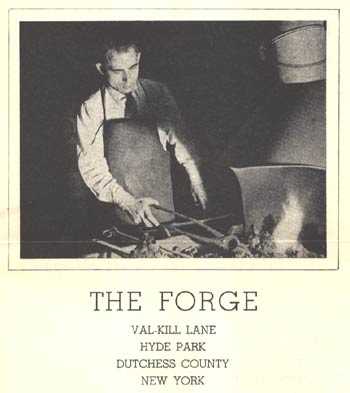

their hands to use in places they lived. Mrs. Roosevelt is

already making replicas of furniture, and in the future we may

see her leading groups of craftsmen in the fields of wrought

metal, cloth, and basket weaving, and perhaps pottery

baking.

|